Sasanka Perera

(This essay was initially published in The Island on 24 December 2025:

https://island.lk/the-aesthetics-and-the-visual-politics-of-an-artisanal-community/)

Organized by the Colombo Institute for Human Sciences in Collaboration with Millennium Art Contemporary, an interesting and unique exhibition got underway in the latter’s gallery in Millennium City, Oruwala on 21 December 2025. The exhibition is titled, ‘Through the Eyes of the Patua: Ramayana Paintings of an Artisanal Community’ and was organized parallel to the conference that was held on 20 December 2025 under the theme, ‘Move Your Shadow:

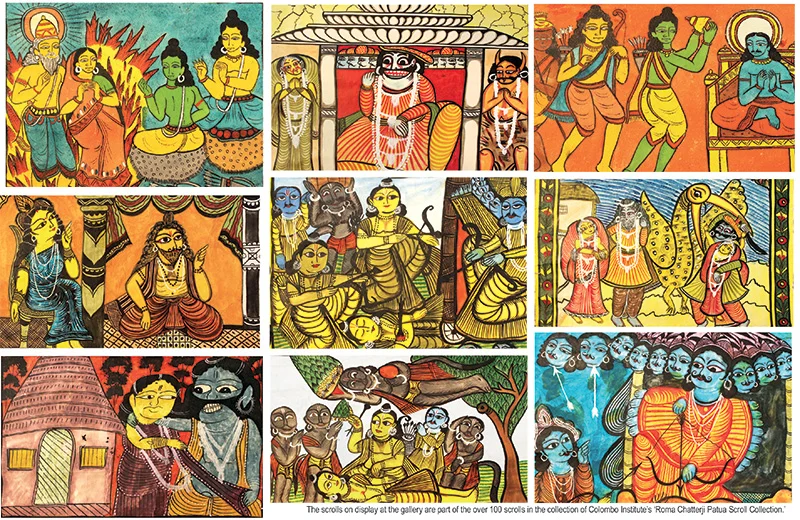

Rediscovering Ravana, Forms of Resistance and Alternative Universes in the Tellings of the Ramayana.’ The scrolls on display are part of the over 100 scrolls in the collection of Colombo Institute’s ‘Roma Chatterji Patua Scroll Collection.’ Prof Chatterji who taught Sociology at University of Delhi and at rest teaches at Shiv Nadar University donated the scrolls to the Colombo Institute in 2024.

The paintings on display are what might be called narrative scrolls that are often longer than ten feet or more. Each scroll narrates a story, with separate panels pictorially depicting one component of such a story. The Patuas or the Chitrakars, as they are also known, are traditionally bards and while a rolled-up scroll is unfolded a bard will sing the story that is meant to be narrated by each scroll. For Sri Lankan viewers for whom the paintings and their contexts of production and use would be unusual and unfamiliar, they best way to understand them is to consider them as cartoon stories. But since the bards or the songs sung with the scrolls are not part of the exhibition, the word and voice element is missing. However, the curators have thoughtfully ensured some element of this is still understood by giving a series of video presentations of the songs, how the singing is done accompanied by scrolls and the history of the Patuas as part of the exhibition itself.

Precisely because of the unfamiliarity of the art on display and their histories, boarder explanation is needed. This particular community of artisans are from Medinipur District of West Bengal in India. Essentially, they are traditional painters and singers who compose stories based on sacred texts such as the Ramayana or Maha Baratha as well as secular events that can vary from the bombing of the Twin Towers in New York in 2001 to the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004. Even though painting is done by a number of traditional artisan groups in Bengal, the Patuas are the only ones who also performed by singing and displaying their scrolls. This is why Professor Cahhetrji, in her curatorial note for the exhibition calls them “the original multi-media performers in Bengal.”

The story of the Patuas also paints the story of what happens to such artisanal communities in contemporary times in South Asia more broadly even though this specific story is from India. There was a time before the 21st century when such communities were living and working across a large part of eastern India – each group with a claim to their recognizably unique style of painting. However, at the present time, this community and their vocation is limited to areas such as Medinipur, Birbhum, Purulia and Dumka in West Bengal.

One also has to ask the question, how the scroll painters from Medinipur have survived the vagaries of time when others have not. Professor Chatterji provides an important clue when she notes that these painters, “unlike their counterparts elsewhere, are also extremely responsive to political events.” As such, “apart from a rich repertoire of stories based on myth and folklore, including the Ramayana and other epics, they have, over many years, also composed on themes that range from events of local or national significance such as boat accidents and communal violence to global events such as the tsunami and the attack on the World Trade Centre.”

There is another interesting aspect that becomes evident when one looks into the socio-cultural background of this community. As Professor Chatterji writes again in her note, “one significant feature that gives a distinct flavor to their stories is the fact that a majority of Chitrakars consider themselves to be Muslims but perform stories based largely on Hindu myths.” In this sense, their story complicates the tension-ridden dichotomies between ethno-cultural and religious groups typical of relations between groups in India as as well as more broadly in South Asia, including in Sri Lanka. Prof Chatterji suggests this positionality allows the Patua to have “a truly secular voice so vital in the world that we live in today.”

As a result, as she further notes, contemporary Patuas “have propagated the message of communal harmony in their compositions in the context of the recent riots in India and the Gulf War. Their commentaries couched in the language of myth are profoundly symbolic and draw on a rich oral tradition of storytelling.” What is even more important is their “engagement with contemporary issues also inflects their aesthetics” because many of these painters also “experiment with novel painterly values inspired by recent interaction with new media such as comic books and with folk art forms from other parts of the country.”

From this varied repertoire of the Patuas’ painterly tradition, this exhibition focusses on scrolls portraying different aspects of the Ramayana. In North Indian and the more dominant renditions of the Ramayana, the focus is on Rama while in many alternate renditions this shifts to Ravana as typified by versions popular among the Sinhalas and Tamils in Sri Lanka as well as in some areas in Indian states of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and places like Jodhpur in Rajasthan and in the tribal areas of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and West Bengal. Compared to this, the Patua renditions in the exhibition mostly illustrate the abduction of Sita with a pronounced focus on Sita and not on Ravana, the conventional antagonist or on Rama, the conventional protagonist. Instead, both these figures are distant. But with the focus on Sita, these folk renditions also bring to the fore other figures directly associated with her such as her sons Luv and Kush in the act of capturing Rama’s victory horse as well as Lakshmana.

But almost as a counter narrative to these Ramayana scrolls and as a comparison the exhibition also presents three scrolls known as ‘Bin-laden Patas’ depicting different renditions of the attack on New York’s Twin Towers.

This is the first time painted scrolls linked directly to the traditional Patua or Chitakar artistic traditions of West Bengal, India are being exhibited in Sri Lanka while the scrolls from this collection have been exhibited three times in India earlier. Organized with diplomatic or political leanings purely as a Sri Lankan effort, it is worth a visit. It will run until 10 January 2026.