(This essay was initially published in The Island on 13 November 2025: https://island.lk/the-art-of-diplomacy/)

On 8th November 2025, I visited the residence of the Swiss ambassador for the opening of the ‘Art Collection of the Swiss Residence in Colombo’ featuring the works of eleven contemporary Sri Lankan artists and an elegant reproduction of the well-known 1951 Goerge Keyt painting, ‘Kangodi Ragini’. All works were loaned by local collectors or the artists themselves. This is one of two diplomatic residences in Colombo where a collection of Sri Lankan art in this format and magnitude has been showcased, the other being the residence of the US ambassador.

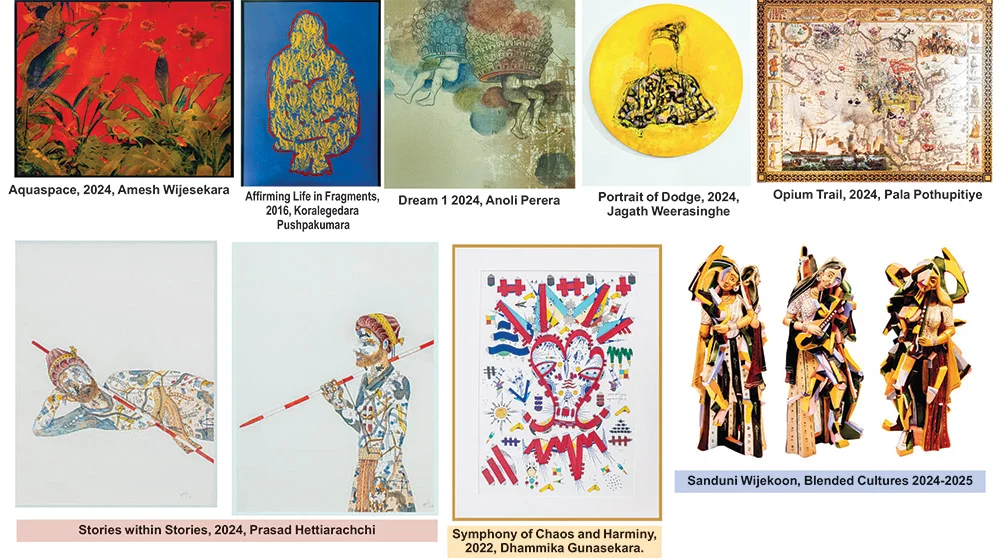

The curator for both collections, Suresh Dominic, one of Sri Lanka’s best-known and eclectic collectors, notes in the exhibition catalogue at the Swiss residence, “the collection brings together modern and contemporary works by world-renowned as well as emerging Sri Lankan artists, encompassing sculptures, paintings and tapestries.”

The exhibition also includes the works of Swiss artist, Marie Schumann, as a part of the residence’s permanent collection. Swiss Ambassador Siri Walt notes in the same catalogue that Schumann’s work “enters into a dialogue with twelve distinguished Sri Lankan artists on themes of history, identity and cultural exchange.” The Sri Lankan artists represented in the exhibition other than Keyt include Sanduni Wijekoon, Pradeep Thalawatta, Koralegedara Pushpakumara, Jagath Weerasinghe, Amesh Wijesekera, Anoli Perera, Pala Pothupitiye, Chathurika Jayani, Prasad Hettiarachchi, Arulraj Ulaganathan and Dhammika Gunasekara.

Crucially, Ambassador Walt also reflects on what art can do in diplomacy when she writes “… this exhibition highlights the role of art in diplomacy – fostering dialogue, reflection, and mutual understanding.” While viewing the exhibition, and the effort taken to showcase Sri Lankan work, I was simultaneously struck and saddened by the sheer lack of such institutional encouragement within Sri Lanka’s diplomatic network across the world, some of which are located in central urban spaces and iconic buildings. This is despite the fact that contemporary Sri Lankan art has much to offer and is already included in major international collections in the public and private sectors. These include the Fukuoka Museum of Asian Art; Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Delhi; Museum of Art and photography, Bangalore; Queensland Museum, Brisbane; The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi; Ishara Arts Foundation, Dubai; Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery, Lancashire; Museum der Weltkulturen, Frankfurt; Weltmuseum Wien, Vienna, Cinnamon Life, Colombo, among many others. This list does not even include the many more private collections scattered across the world.

Walking through the exhibition, I was also reminded of the 2009 book by Christine Sylvester titled, Art/Museums: International Relations Where We Least Expect It. The basic logic in the title of this book has obviously been grasped by the two foreign ambassadors in Sri Lanka. In fact, many countries have formalized systems of acquiring art from their countries to give cultural context and nuance to their embassies, residences, cultural centers and other diplomatic offices around the world. This aims to promote their own art abroad. Significantly, the Swiss and US collections go above and beyond this, as they aim to promote not only their art, but also ours. Equally crucial is that these two collections can take selected Sri Lankan art, knowledge about them and their creators to viewers and aficionados in the diplomatic and development sectors as well as the country’s business elites who frequent such spaces. In other words, this is a potential avenue to not only showcase Sri Lankan art but also a means to expand the market for them.

What about art promotion as part of Sri Lanka’s diplomatic effort itself? Over the years, I have had informal conversations with several of our senior diplomats about doing precisely this. While they all acknowledged there was no system in place to do this, and that it indeed is a good idea, there was clearly no enthusiasm. After seeing the interiors of many Sri Lankan missions and residences I had visited in different countries, it was evident to me that many of them had no serious understanding of Sri Lankan visual art, in particular, or our cultural terrain, more generally, beyond the conventional understanding of art and culture of many ordinary citizens. This is why for example, up to 2024, the Sri Lanka High Commission in Delhi and the residence of the High Commissioner had as part of their permanent interior décor framed fading posters of the Sri Lanka Tourist Board depicting temple paintings and Sigiriya frescos and a specially commissioned painting by Prasanna Weerakkody showing the arrival of the sacred bo sapling from ancient India in the Kingdom of Anuradhapura. Weerakkody is well-known in Sri Lanka for executing popular paintings of muscular men in action-hero poses in historically mismatched costumes and backdrops supposedly depicting the country’s past. As a populist genre, his work is found in numerous public buildings and private collections.

However, compared to the kind of artists featured in the US and Swiss collections in Colombo whose works are also in the collections of the museums noted above, Weerakkody’s painting in the Sri Lanka High Commission in Delhi is a sad testament to our diplomats’ sub-par understanding of contemporary art and that too in a city that is a major global cultural and art hub.

Along a similar vein, in the same premises in 2015 President Maithripala Sirisena unveiled a replica of the 8th century BC Avalokitheswara Bodhisathwa statue at the invitation of former High Commissioner Sudarshan Seneviratne. The original gold-plated bronze statue discovered in Weragala, is an iconic and globally accoladed example of the recognizably Sri Lankan tradition of bronze sculpture. While it did not promote contemporary Sri Lankan art it did what it was expected of it, which was to offer a point of departure for conversations on Sri Lankan history, culture and statuary. Is this not an essential aspect of an embassy’s role — the promotion of our culture and history? But regular Indian visitors to the High Commission who admired the sculpture now tell me it has simply disappeared and has been replaced by a bunch of common flowering plants.

At the current juncture however, there is a declared interest by the government towards ushering in a cultural revival in the country which also includes expanding tourism to include art and other forms of local culture. NPP’s election manifesto talks about “developing Art Tourism and Cultural Tourismwithin its national cultural and tourism policies” and goes on to refer specifically to the “Art and Creative Industries Policy” which includes an interest to “develop galleries, theatres, open-air stages, and digital archives” while linking the “arts and creative sectors with tourism to promote exhibitions and markets.” Moreover, I have heard the Minister of Culture often referring to art tourism, which is a good sign. I have also heard the same being discussed among several local collectors. But I have not seen a clear actionable policy so far making this idea operational on the ground.

The highly successful charity auction organized by the George Keyt Foundation in collaboration with Sotheby’s in December 2024 at The Forum, Cinnamon Life is a practicable example of how to promote Sri Lankan art locally and globally and within a paradigm that combines tourism and commerce. It clearly showed the local and regional interest in Sri Lankan art, the nature of the market and income-generating potential. Similarly, it is noteworthy that at least two Sri Lankan banks, the Nations Trust Bank and Sampath Bank have specific programs to promote art among their clients and offer them the means to purchase local art. What does this indicate? Art promotion is no longer mere charity events to help artists. Instead, art is a matter of promoting Sri Lankan culture within high-end tourism through the global circulation of cultural objects with significant value, embedded within government policy. In more blunt terms, art is about opening newer avenues for generating income for people and the country at a time when hard currency is crucial to our economy.

This said, the government’s interest in reviving the Arts Council Act to make the Arts Council of Sri Lanka a more robust cultural entity on par with successful organizations of the same kind elsewhere in the world, and the Prime Minister and the Minister of Culture spending considerable time at the recently concluded international art exhibition, Feminist Futures: Art, Activism, and South Asian Womanhood’ in Colombo are encouraging signs of considerable enthusiasm towards the arts among some of our political leaders.

But there are no signs yet of this enthusiasm extending to our diplomats in the way the US and Swiss ambassadors have shown. Even the dilapidated but elegant Foreign Ministry building and its uninspiring and culturally barren interiors are an example of this sad state of affairs in the same way the interiors of the Sri Lanka High Commission and residence in Delhi have been for decades. But one must note the Sri Lankan diplomatic facilities referred to here is only one of many examples of the same ilk.

On the other hand, given the way many government offices generally work, including the Foreign Ministry, burdened by systematized inefficiency which kills whatever enthusiasm some officers may have, ensures that the kind of interest shown by the Swiss and US ambassadors will not come from them naturally, knowing well the kind of obstacles they will face within.

Hence, there needs to be clear signals from the country’s political leadership to the Foreign Ministry that its missions abroad must promote Sri Lankan arts and culture in the same way mainstream tourism is often promoted by these same entities. Ideally this should come at the present time when our private collectors have become far more culturally enlightened and globally connected than any time in the recent past, and also have an interest in promoting art not only as a matter of aesthetics but also as a matter of tourism and investment in a climate when the government is also receptive to such activities. But for this, the government cannot bank on its unenlightened party workers with their stunted cultural understanding or diplomatic officers whose cultural sensitivities and enthusiasm have been blunted over the years.

In this context, this can only come as a policy that is drafted by people who understand Sri Lankan contemporary art, are sensitive towards structures of taste within the country and beyond, and know how the art markets work in the region and elsewhere. But such a policy will only bear fruit if mechanisms are in place to ensure its implementation. It is also important to note this kind of cultural diplomacy can be activated through our missions abroad with relatively small budgets and with the backing of the corporate sector as long as these activities are planned within a sensible and viable commercial context without compromising the vitality and complexity of Lankan art.

One can only hope that our political leaders might for once show enlightenment to ensure the entities under their purview do more than the uninspired and humdrum cultural outreach, merely paying lip service to promoting Sri Lankan art and culture abroad.

Mr. Minister of Foreign Affairs & Tourism, “quid cogitas?”